The exhibition NSK from Kapital to Capital covers a period that marked the final decade of Yugoslavia, highlighting the fact that NSK was no less a critic of the coming global capitalism than of the failing outgoing socialism. In the latter respect it differed both notably and fundamentally from the liberal critique of socialism. Rather than employing the standard forms of artistic critique or irony, NSK based its approach on subversive affirmation and over-identification, articulating, among other things, the kind of society the groups envisioned after the collapse of socialism. Founding the NSK State in Time in 1992, they opted for a global community based not on territorial or economic principles but on aesthetics and thought.

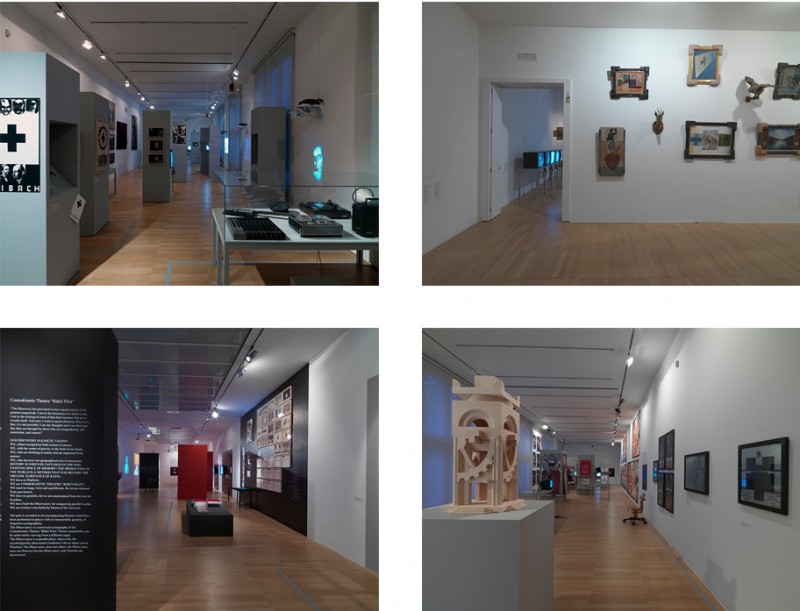

Photo: Dejan Habicht

In 1990, the Cosmokinetic Cabinet Noordung (the successor of the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre and Cosmokinetic Theatre Rdeči pilot) staged a production entitled Kapital; in 1991, IRWIN published a book and staged an exhibition entitled Kapital; and in 1992, Laibach released an album entitled Kapital. With these projects the three core NSK groups marked the end of ideology and the beginning of total capitalism, which many continue to see as a social system without an alternative. Not so NSK: it has already established itself as an alternative institution and an alternative state, in both the concrete and abstract senses of the word.

In the 1980s, NSK built its subjectivity through the deconstruction of various traumatic absences in Yugoslavia: the absence of the emancipatory potential of struggle for liberation, the absence of workers’ rights, the absence of an original national culture, and the absence of a developed art system and a strong state. In order to find a substitute for this considerable body of absences it devised, within the framework of its aesthetic concept, a unique principle of construction that is at the same time a principle of deconstruction. NSK generally needs to be understood in terms of its complexity and ambivalence; no NSK work is merely an artefact, a painting, a theatre production, a concert, a publicity action, a provocation – as often as not it is all of these and more all at once. The various media and approaches employed combine to form a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art that transcends the boundaries of the usual understanding of art.

The exhibiting of NSK from Kapital to Capital is designed to trace both the many separate events that developed and the duration of the various concepts at work. Much like the 1980s marked a pivotal decade in politics, with a string of related events leading up to the bloodshed of the war in Yugoslavia in the 1990s, each NSK concert, exhibition, theatre performance or other public appearance triggered processes that have not yet run their course to this day. Employing the philosophical language of Alain Badiou, we could say that the NSK Gesamtkunstwerk was an event that ruptured with the established order of things. Every NSK event was a monolith with multiple meanings, new projects, and references stemming out of it. NSK was not a chronicler of the era; by the same token, however, it cannot be fully comprehended without an understanding of the socio-political context of the 1980s. All too often the work of NSK is associated exclusively with the context of the failing Yugoslavia and socialism, with a general disregard for its artistic reflection, its reflection on broader global processes, and the artists’ fundamental goal: to construct a new artistic constellation that would allow them to enter international dialogues in their own right.

The art of NSK could be compared to such international trends as appropriation art, institutional critique, and relational art, though these descriptions fail to encompass a crucial difference, one that NSK safeguarded by coining its own terms for what it did. NSK countered the postmodern art of the 1980s with its retro method, laying bare the ideological manipulation with images: Laibach with the retro-avant-garde, the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre with the retrogarde, and IRWIN with the retro principle. NSK differed from Western appropriation art in that it appropriated, with its events, the state itself and state institutions; it differed from the familiar paradigms of institutional critique in that it arrived at the conclusion that there was actually nothing to criticize, since both the state and the institutions first needed to be constructed; and it differed from usual relational art in that the NSK events of the early 1990s already involved the participation of others who wanted to see radical changes in the art system and who shared the same sense and set of urgencies regarding the Eastern European cultural space in the new circumstances.

Photos by Dejan Habicht

The NSK principle is embodied, from the very outset, in the collective’s German name, meaning New Slovenian Art and alluding to both “Junge slovenische Kunst”, the title of a special issue of the German avant-garde journal Der Sturm from 1929 featuring young Slovenian art, as well as to the trauma that grew out of more than one thousand years of German political and cultural hegemony over the small Slovenian nation. “New national art” presented itself both as international, i.e., capable of entering the international art arena, and as the cultural product of a small nation that can only thrive once it recognizes its inherent eclecticism based on and in relation to Eastern and Western cultural influences.

What can we take away, what lesson might be gleaned from NSK that could be of use to us today? At first glance, the NSK fusion of mutually exclusive symbols appears to have become an essential part of contemporary imagery. On the one hand, we are witnesses to a process of complete symbolic depletion, and on the other, to the reactivation of symbols.

Today, this game of symbols is becoming uncomfortably similar to that of the dubious 1980s, making the NSK tradition more topical than ever.

Zdenka Badovinac