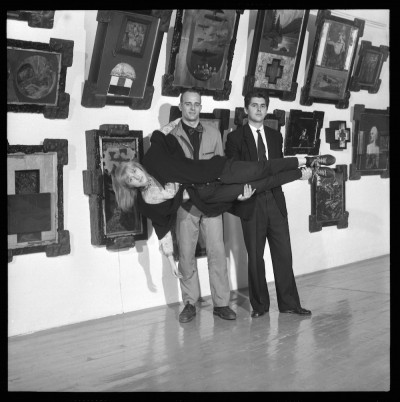

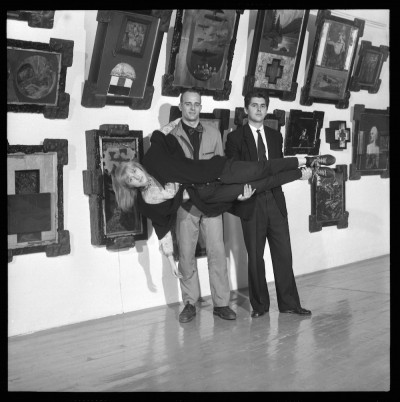

An exhibition at the Equrna Gallery, Ljubljana, 1990, photo by Franci Virant

The Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre was formed on 13 October 1983 in Ljubljana, by members Eda Čufer, Miran Mohar, and Dragan Živadinov. In 1987, the SNST self-terminated and transformed into the Cosmokinetic Theatre Rdeči pilot and in 1990 into the Cosmokinetic Cabinet Noordung. The retrogarde method was employed in all three stages of the theatre.

An exhibition at the Equrna Gallery, Ljubljana, 1990, photo by Franci Virant

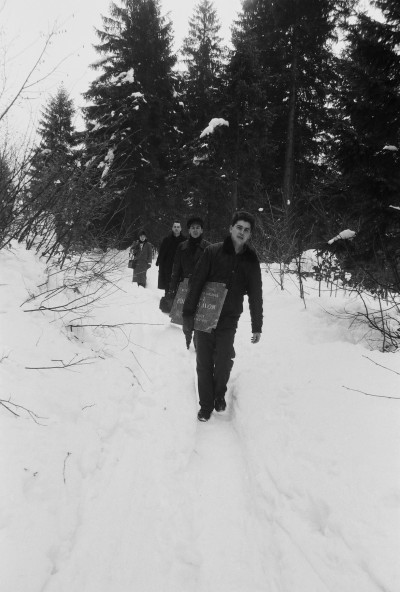

SCIPION NASICE SISTERS THEATRE, Erecting the Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav plaque, the Savica waterfall, Bohinj, 1986, photo by Darko Pokorn

The Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre (SNST) was founded on 13 October 1983 with “The Founding Act”, a programmatic text in which the anonymous members set out the group’s programme, organizational structure and modus operandi, and announced its plan for eventual “self-termination” once its goals had been achieved. The SNST’s basic objective, as stated in “The Founding Act”, was to “revive the performing arts”. To this end, the group launched a three-stage programme divided into a “creative” part (theatrical productions that were unfailingly referred to as “retrogarde events”) and a “manifestative” part (actions and texts aimed at public relations activities). The three stages of the SNST were as follows:

Stage 1: Underground: the group announced its existence and publicly distributed its programme, staged its first production, the Retrogarde Event Hinkemann (1984), and carried out its Resurrection of the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre action.

Stage 2: Exorcism: the SNST staged the production of the Retrogarde Event Marija Nablocka.

Stage 3: Retro-Classical: here, the aim was to break through to one or more stages of national institutions; this was realized with the Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav, produced by Cankarjev dom (and staged in its Gallus Hall).

The events of the various stages were all accompanied by programmatic texts, laying out the SNST’s creative method: it was based on the retro approach (art using art as its creative material, “art from art”), which was also developed by the other groups of the NSK collective. The SNST named its version of this method “retrogarde”, to underscore its active nature and aim to break through from the underground stage to the retro-classical one. In addition to focusing on retrogarde, active, and event-based work, the group also framed (in the “First Sisters Letter”) its programmatic task of analyzing the relation between theatre and state.

Both theatre and state are based on the production of events (performativity); as a result – so the Scipions claimed in their programmes – the methods and the effects of the theatre and the state are often indistinguishable from one another (“Theatre is a State”).

The Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre took its name after the Roman consul Scipio Nasica, who ordered the destruction of a theatre (a point noted by Antonin Artaud). As it had predicted in 1983, the SNST ended its activities between 1986, when it announced its imminent self-termination, and 1987, when it carried out the Act of Self-Destruction (by preparing an unrealized spectacle-event for the Youth Day 1987 celebration). After the self-termination the theretofore anonymous theatre members identified themselves as Eda Čufer (dramaturge), Miran Mohar (set designer), and Dragan Živadinov (director).

In January 1987, the Cosmokinetic Theatre Rdeči pilot was founded. Alluding in its name to Slovenian avant-garde poet Anton Podbevšek’s journal from 1922 (meaning Red Pilot), it was the successor of the Scipion Nasice Sisters Theatre, although with radically different goals, purposes and orientation (laid out in its programme published in the daily Delo). Rather than turning back to history, like the SNST with its retro orientation, Rdeči pilot set its sights on the ultramodern future dictated and shaped by advances in science and technology.

Further, instead of focusing on the event, like the SNST, Rdeči pilot centred on the act of watching and observing (the Observatory), a key part of both theatre and science. The spatial organization of watching, a basic element in theatre, is always treated as a unified space in Rdeči pilot’s projects, rejecting the division between stage and auditorium or actors and spectators, uniting the two poles into a dynamic yet unified space that the director Dragan Živadinov called “inhabited sculptures”. Similar to how SNST had explored the relations between the theatre and state/religion/ritual, Rdeči pilot probed the relations between the theatre and science and technology. In the Drama Observatory Fiat the space was shaped

like a spacecraft simulator, in which the spectators “observed” the action through three apertures that on the one hand organized the gaze like various instruments used in science and technology (camera, microscope, telescope), and on the other symbolized the three fundamental theatrical forms – drama, opera, and ballet. It was through these forms that Rdeči pilot aimed to reconsider the contemporary conditions of man as a being of emotions and instincts, and to observe human adaptation to a world that is transforming into an algorithmic product of rationalized science. In the productions that followed – the Ballet Observatory Fiat (1987), the Ballet Observatory Zenit (1988), the Drama Observatory Zenit (1988), the Opera

Observatory Record (1989, unrealized project), and the Drama Observatory Kapital

(1991) – the director Dragan Živadinov (who made frequent changes to his team of

co-workers in that period of socio-political and aesthetic transition) developed his philosophy and poetics of theatre space (“inhabited sculpture”) down to the last details, and deepened the understanding of the relation between the theatre and science and technology. In 1991 the Drama Observatory Kapital was staged, in which the “cabinet” of the Slovenian pioneer of space science Herman Potočnik Noordung (or rather, the spatial logic of his geostationary satellite, in dialogue with the spatial logic of suprematist and constructivist art) was presented, and this process led to a spontaneous transformationof the Cosmokinetic Theatre Rdeči pilot into the Cosmokinetic Cabinet Noordung. Dragan Živadinov explained this transformation at a five-hour press conference (performance), also presenting his plan of work until 2045 to the journalists. Among the items on his agenda (called “detonations”) there was also the systematic mythologizing of Herman Potočnik Noordung, whose scientific work and pioneer spirit Živadinov set out to honour not only with theatrical productions like the Prayer Machine Noordung (1992), but also by taking other actions. The latter started in the early

1990s with Slovenian and English translations and international distribution of Potočnik’s book The Problem of Space Travel: the Rocket Motor, and culminated with the opening of KSEVT, the Cultural Centre of European Space Technologies, in Vitanje, Slovenia in 2010.

COSMOKINETIC THEATRE RDEČI PILOT, Drama Observatory Zenit, 1988, photo: Franci Virant

COSMOKINETIC CABINET NOORDUNG, Cosmokinetic Ballet Prayer Machine Noordung, 1992, photo by B.G

COSMOKINETIC CABINET NOORDUNG, Cosmokinetic Ballet Prayer Machine Noordung, 1992, photo by B.G

SCIPION NASICE SISTERS THEATRE, Retrogarde Event Marija Nablocka, 1985 Photo: Marko Modic

SCIPION NASICE SISTERS THEATRE, Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav, 1986, photo by Marko Modic

SCIPION NASICE SISTERS THEATRE, Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav, 1986, photo by Marko Modic

SCIPION NASICE SISTERS THEATRE, Retrogarde Event Baptism under Triglav, 1986, photo by Marko Modic